Whitby Abbey is a special place. The abbey dominates the landscape from its exposed location on top of the cliffs. The ruins of the Benedictine monastery visible today were originally built in the 11th century, in the place of the first double monastery founded by St Hilda on land at Streanæsalch given to her by King Oswiu in 675 (if you want to know how to pronounce Streans…, you know what I mean, please listen to the BBC series about men and women of Anglo-Saxon time; you can find the link in the reference list at the end of this blog). St Hilda was raised by King Edwin of Northumbria after the killing of her father. Her importance lies in the influence she had while residing over the Synod of Whitby in 664, setting the direction of Christianity in England for the future. She is known as an adviser to kings and bishops, and Bede gives very detailed reports of her role in politics. She was succeeded by Oswiu’s widow Queen Eanflæd and their daughter Ælfflæd. Caedmon’s cross at the church of St Mary’s next to the Abbey stands for the first English poet whom St Hilda inspired to create poems for the best use of his heavenly gift.

St Hilda founded convents in various places, and on my journey north, I am not able to visit all of them. But after Hackness, I decided to visit St Peter’s Church at Monkwearmouth, perhaps the place where St Hilda ‘entered monastic life’. But, today, the place is better known as the home of the venerable Bede. Nevertheless, the lower part of the tower and the arched entrance dates to 674-5 and the first church in this location. What a strange feeling to touch stone that has perhaps also been touched by St Hilda and Bede (definitely goosebumps time). The extent of the first monastery is outlined by small walls on the ground and give an impression of the landscape as it had been constructed in the 7thcentury. Unfortunately, the church is locked and leaves me with a strange feeling that we have not only lost access to buildings but to space for inner reflection, peace and contemplation.

On to Coldingham, I stop at Coldingham Priory, where Æbbe the Elder (and the Younger, perhaps a legend rather than a real person) and Æthelgyth were located. The priory lies in a beautiful gently undulating landscape, alternating fields and small woodland, and close to a stream. The original double monastery founded around 635 by St Æbbe lies beyond the graveyard and was excavated by Digventures. You can read everything about this exciting project here: https://projects.digventures.com/coldingham-priory/background/an-unusual-tale. After several episodes of destruction and rebuilding, the 13th century remains are beautifully preserved and information boards are everywhere around the site.

At the northernmost points of my journey, I visit the places associated with St Margaret, patron saint of Scotland. Margaret, a Saxon princess, born in 1045, was a descendent of King Alfred the Great. She was born in Hungary to Edward Aethling the Exile, son of Edmund II Ironside, and Agatha, niece of the Holy Roman Emperor Henry III. The family, including her sister Cristina (later Abbess of Romsey) and her brother Edgar the Aetheling, returned to England in 1057 on invitation of Edward the Confessor, who was without heirs. However, after the death of her father and with a potential threat to her brother’s life, following the invasion of William the Conqueror in 1066, the family fled again and ended up in Scotland at the court of Malcom III, King of the Scots. Malcom married Margaret, who was, according to her biographer Turgot (later Bishop of St Andrews), famous for her piety, learning, beauty, mercy, and sense of justice. At the place of their marriage, Margaret founded a priory for Benedictine monks, and David I elevated the place to an Abbey in 1128. Margaret of Scotland had 8 children, all of whom became Kings or Queens. She died in 1093 at the age of fourtyeight just days after her husband and son (killed at the battle of Alnwick).

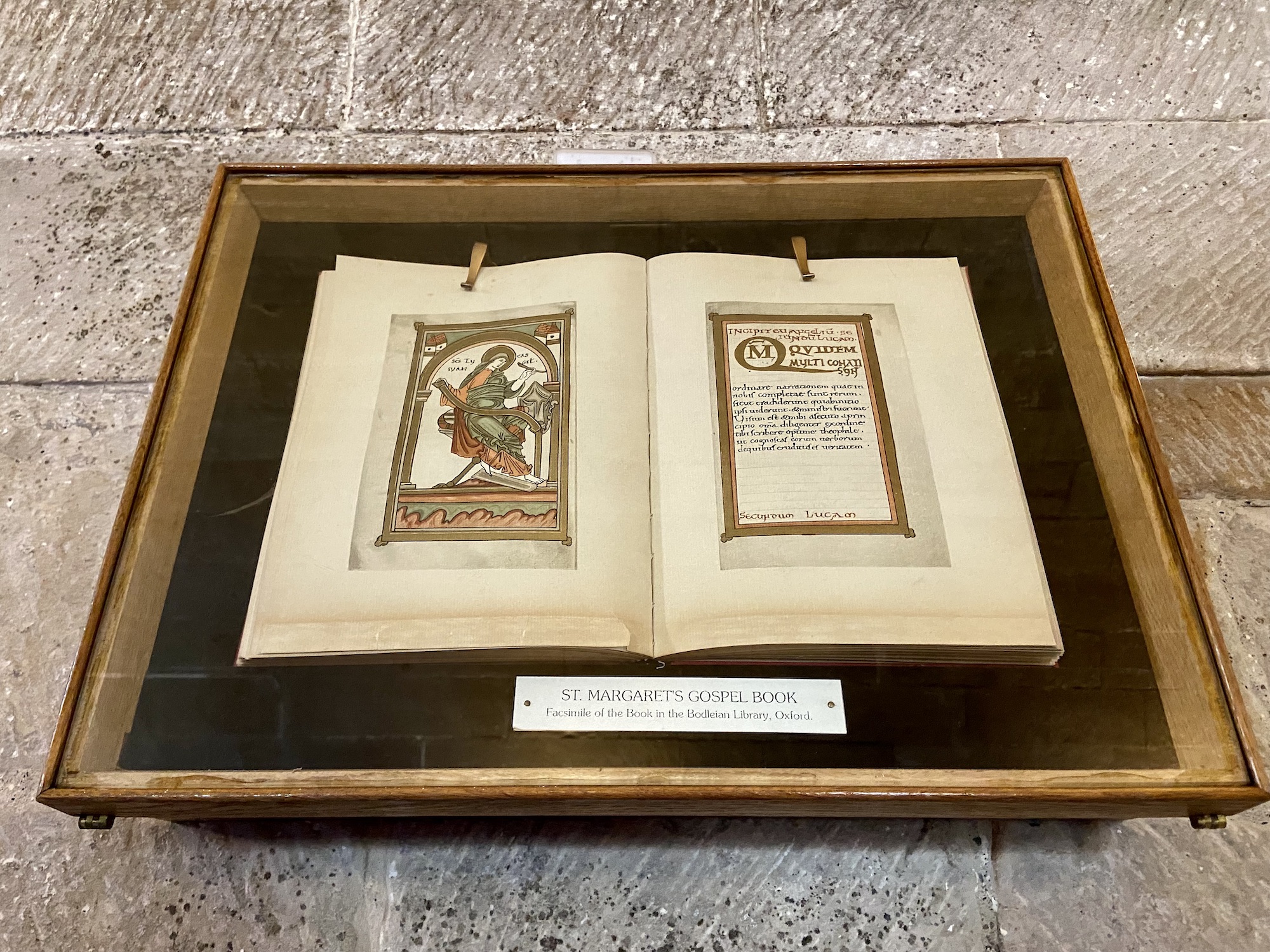

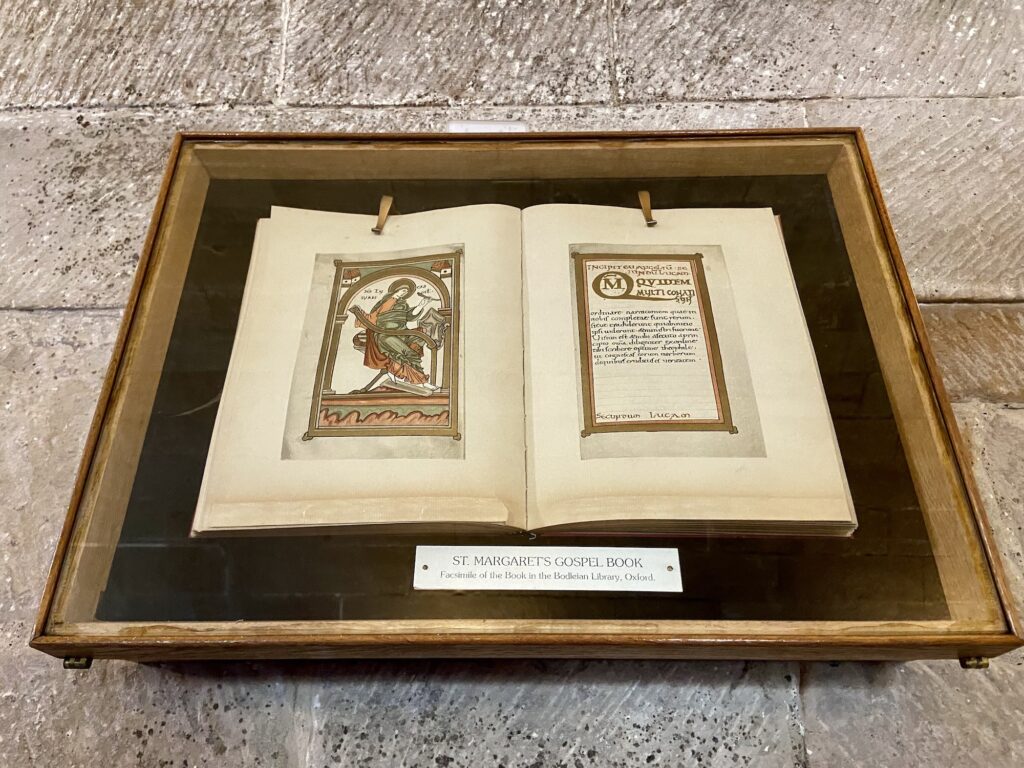

I stop at Edinburgh Castle first to record the sites where she lived, worked, and was buried. The castle glistens in the sunshine against the dark blue sky. No signs of the storm just gone or the next one to arrive soon. The castle was temporarily closed due to strong winds in the morning, but when I arrived, Edinburgh presented itself from its most beautiful side. The castle is an impressive site, but I am only interested in the smallest building of the complex: St Margaret’s Chapel. The chapel is the most ancient part of the castle and probably part of the ‘great stone tower’ built in about 1130 and dedicated to his mother by David I. The chapel almost feels like a cave, a warm, safe and secure place, in its unostentatious modesty, and I have a sense of calmness, warmth and relaxation. The rush of the busy castle swamped by tourists seems to be shut out. The sun illuminates the stained glass window of Margaret. I am fascinated by the display of Margret’s prayer book at one side of the chapel. I am sure this small but welcoming place would have been a haven of peace and contemplation in a buzzing castle of the old days.

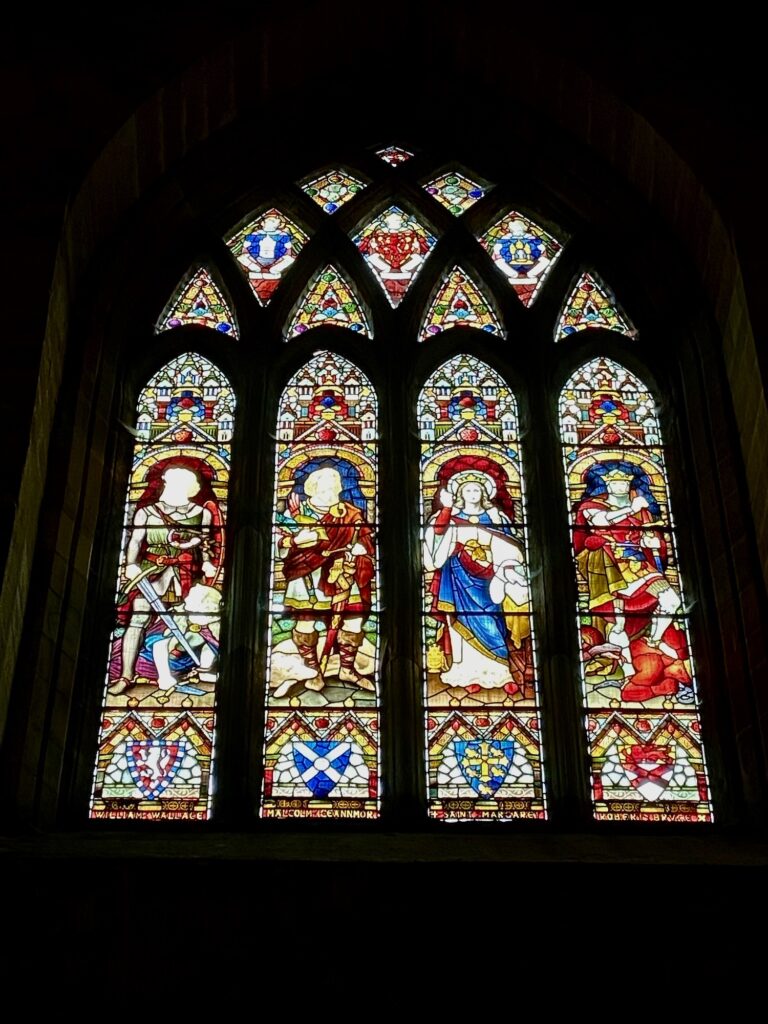

My second and last stop in Scotland brings me to Dunfermline to visit the tomb of St Margaret at the eastern end of the abbey. Her bones were reinterred here after being moved out from the earlier abbey during the excavations for the later extension. The exterior is an amazing testimony to the evolution of the place. I am always an early bird, and as there had been weather warnings for a snow blizzard (which did not come), I am the only visitor at opening time. So, I have the abbey for myself, and the guide Farrell from Historic Environment Scotland shares his broad knowledge on Margaret and all the places associated with her only with me. Margaret’s first church was identified during excavations and is marked on the floor. Two stone sarcophagi of her sons are placed against one wall. The abbey is otherwise empty. Buildings like this have a very special atmosphere. The building emanates sombre grace, peacefulness and calm. Despite the enormous space, one does not feel lost, quite the opposite. I feel calm and safe. The windows allow an array of colourful light into the space. It is comfortably warm, keeping the chilly air out. It smells of stone and ancient times – a good smell. The noises of the town are shut out. For a moment, you might think: all will be good…

Back in the real world, I follow the advice of my guide Farrell and visit the remains of the tower where Malcolm and Margaret had lived and where she had born her children and, astonishingly enough for this time, had raised all to adult age. Malcolm Canmore’s Tower stands just 100 yards from the abbey to the west. Finally, I visit St Margaret’s Memorial church in town, where, so I was told, I would find a relic of St Margaret: her collar bone. The modern church feels very different. It is colourful in a different way and smells of incense, images and songbooks. Carpet and cushions everywhere. I think it is a bit too bright, too distracting. It cannot quite give me the same feeling as the modest old building, this cave-like, secure sanctuary. The priest is lovely and shows me around. In the lady chapel, he presents the relic and a glass bottle with sand from the place in Hungary where Margaret was born. It might be the archaeologist in me that would choose the old building over the new for inner contemplation. And through my visits to old churches, I become more and more aware that this blog will tend to be an appeal to preserve the old structures even if it is a challenge. These buildings are not just stone and mortar but expressions of techniques, skills of people and times long gone that cannot be replaced by modern equivalents – the genius loci that reside in places, some call it spirit, some magic.

I travel southwards on the west side to stop at St Bees priory associated with St Bega, as mentioned in my last blog, in connection to her (almost namesake) the nun Begu at Hackness. St Bees priory does not mention the saint in its history anymore. All attention is now on the St Bees man discovered in the collapsed chancel aisle during an excavation of Leicester University in 1981. The man who could not be reliably identified was extremely well preserved. He had died between 1290 and 1500. If the assumption is correct that St Bega was an attempt to raise the prestige of the priory and connect it to a person mentioned by Bede, this legend is not needed anymore with a find such as the St Bees man.

My northern round to explore the places where Anglo-Saxon female saints had lived, worked and died finds its end with St Alkelda. Not much is known about her, but Blair and Farmer mention her legend, that she was a princess (perhaps a daughter of King Oswiu). She was strangled by a Viking woman and buried at the church of Middleham. Two churches are dedicated to the rather obscure saint: Giggleswick and Middleham. The church of St Alkelda at Giggleswick is a Grade I listed building mainly built in the 14/15th century. The same is applies to the church of St Mary and St Alkelda at Middleham. Both are great examples of medieval churches but rather difficult to associate with the saint they are dedicated to.

This round trip, exploring the places associated to Anglo-Saxon female saints, has turned histories and legends into living and breathing places where people today are as fascinated by the women that founded or inspired the religious communities. They set a permanent mark on the landscape and are continuing to inspire people to this day. Nowhere else was this feeling of continuing inspiration and veneration stronger than at the places and with the people connected to St Margaret in Dunfermline. What a testimony for the achievements of a woman, 929 years after her death. As Barbara Yorks points out, it was an extraordinary time of transition that offered women opportunities to lead double monasteries and teach men and play a vital part in politics beyond being just pawns in political alliances. However, the extraordinary women of the time took the opportunities to shape the future and change the world.

References

Yorke, Barbara. Nunneries and the Anglo-Saxon Royal Houses. London: Continuum, 2003.

Yorke, Barbara Hild of Whitby. Anglo-Saxon Portraits. Thirty Ground-Breaking Men and Women of the Early English Nation, BBC 2020

Blair J., ‘A Handlist of Anglo-Saxon Saints’, in Local Saints and Local Churches in the Early Medieval West, ed. Alan Thacker and Richard Sharpe (Oxford University Press 2002), 495-566

Farmer 2011, Oxford Dictionary of Anglo-Saxon Saints

https://www.historicenvironment.scot/visit-a-place/places/dunfermline-abbey-and-palace/history/

http://www.stmargarets-church.co.uk/church-information/who-was-st-margaret-scotland

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1157303?section=official-list-entry