Cities and towns are fascinating places. Urban landscapes are palimpsests of the traces left behind by generations that lived, worked and died in the tangle of buildings, alleys and streets. These traces are only visible to those who can read the landscape… or have the great privilege to have it read to them by an expert. I meet Prof Barbara Yorke at the Buttercross (historical landmarks are perfect meeting points). On the way to the cathedral, Barbara points out several narrow alleys that reflect the Anglo-Saxon layout of Wintancaester (Winchester).

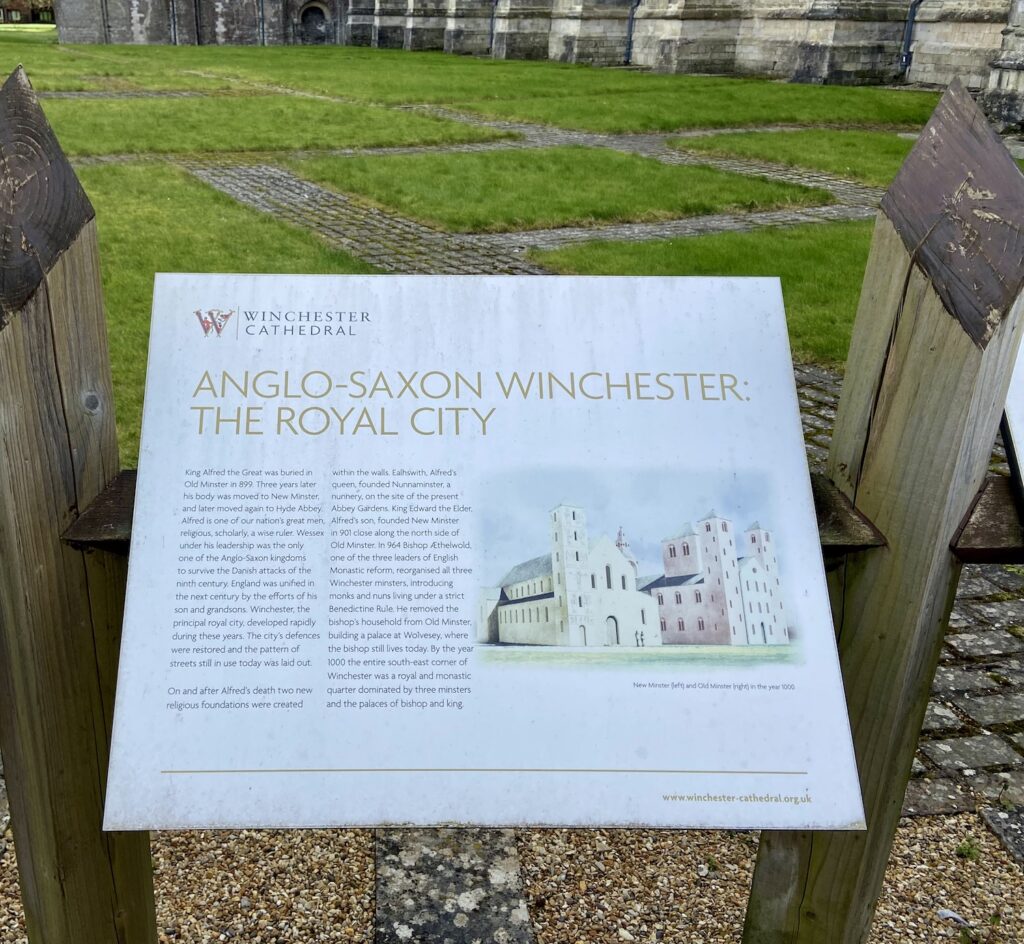

The monastic landscape of Winchester was dominated by three monasteries, Nunnaminster, the Old Minster and the New Minster. This part – including abbey mills and mill streams, feeding fish ponds – formed a religious centre secluded from the growing town. Millstreams are still a dominant feature of Winchester today. The outlines of the foundations of Nunnaminster built c. 903 (later St Mary’s Abbey) founded by Queen Ealswith, the wife of King Alfred the Great, can be seen in the Abbey Gardens where the structures uncovered during an excavation show the various phases from the first wooden church of Ealswith to the Norman Abbey dedicated to St Mary and St Edburga. The exact extent of Queen Ealswith’s estate between Market Street, Middle Street, and the River Itchen is recorded in the Book of Nunnaminster (a prayer book from the 8th century, added in the 9th century). The present layout of the estate and the outline of the Old Minster – on a slightly different angle than today’s Minster – can best be seen on the satellite imagery of Google Earth/Google Maps.

St Edburga was the daughter of Edward the Elder and his third wife Eadgifu of Kent. Legend has it that Kind Edward decided to let her choose her future when she was just three years old. He sat her on his knees before a table with rings and bracelets on one side and a chalice and a book of prayers on the other. Young Edburga chose the chalice and prayer book and became a nun for the rest of her life at Nunnaminster. A sarcophagus excavated in the first church of Nunnaminster might have contained her remains. However, Barbara points out that women in the religious context of Anglo-Saxon monasteries and nunneries were perhaps not how we imagine nuns today. They were women with royal ancestry, influence and connections. They were perhaps wearing colourful garments of fine cloth and jewellery. Artefacts from a high-status burial of an Anglo-Saxon woman in the museum give an impression of how this might have looked. Nunnaminster was a centre of learning and training. Women had great opportunities at this time, as I mentioned in my blog about St Hild and St Margaret.

We visit the statue of King Alfred the Great and admire the artful representation of the king created by Hamo Thornycroftand erected in 1901. Continuing on with our tour, we follow the city wall with remains of the Roman masonry and the Anglo-Saxon reinstatement in the typical herringbone pattern. We pass Jane Austen’s house, where she lived and died (which is another story) and come back into the monastic part of Anglo-Saxon Winchester through the city gates.

Winchester Cathedral is a magnificent building, but as an archaeologist, I am fascinated by the representation of buried/uncovered remains of the Anglo-Saxon era and the traces inscribed in today’s landscape. This was a very special city tour back in time to a place where women played a vital role in religious, political and social life.

References

Blair J., ‘A Handlist of Anglo-Saxon Saints’, in Local Saints and Local Churches in the Early Medieval West, ed. Alan Thacker and Richard Sharpe (Oxford University Press 2002), 526.

Farmer 2011, Oxford Dictionary of Anglo-Saxon Saints (Eadburh)

https://archive.org/details/bishopswinchest00hervgoog/page/n109/mode/2up

https://www.cityofwinchester.co.uk/history/html/nunnaminster.html

https://www.cityofwinchester.co.uk/history/html/king_alfred.html